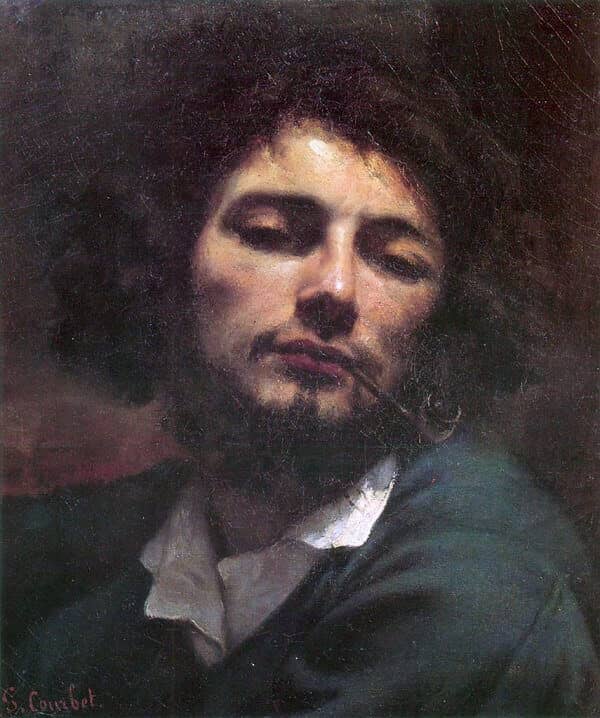

Man with a Pipe, 1848 by Gustave Courbet

Of all the open or disguised self-portraits of Courbet's first decade as a painter, Man with a Pipe is the best known. It was well received from the beginning, despite its being shown at the

Salon of 1850 - 51 in the company of the radically disturbing The Stonebreakers, A Burial at Ornans.

Courbet's great patron, the Montpellier collector Alfred Bruyas, bought it from the artist in 1854, the year following his first Courbet purchases. In a letter to Bruyas of that year the painter

described the work as "the portrait of a fanatic, an ascetic ... of a man disillusioned with the stupidities that have served as his education, and who seeks to establish himself in his principles."

This is a remarkably accurate perception, particularly for a young artist to make about his own self-image, and it reveals the growing maturity of Courbet's mind. As Philippe Bordes remarks,

fanaticism and asceticism accurately describe the intensity of the young painter's project, which could only succeed through absolute conviction and the willingness to withstand temptations to

compromise. The image he presents is in its details that of Bohemian Paris: the artist with his thick and rather wild hair, scruffy beard, pipe, and casual dress. But these are held together by

something much more complex and more difficult to describe: the expression of the face, which is a map of the artist's mind. The head is close, it is thrust aggressively into the viewer's space,

yet while physically close it is mentally remote, its energies focused within, on the content of the gaze.

Dark backgrounds were widely used in portraiture to enhance the three-dimensional effect of the figure. In fragment 232 of his Treatise on Painting, Leonardo da Vinci had noted that a dark background makes an object appear lighter and vice versa.

Of all the exploratory self-portraits of the 1840s, this one is both the least theatrical and the most ambiguous. One is tempted to say that in this painting the self is presented not as playing a role or as fusing cultural identities, but as the man Courbet had become after nearly a decade of work, sustained essentially by his own belief in his Realist project.